DIDs and VCs don’t create digital identity — they create an open, portable, cryptographically verifiable way to represent and share it. They’re still proxies — but they’re user-owned, privacy-preserving, and platform-neutral proxies.

By creating a framework for representing and proving identity they’re a key part of the infrastructure a true identity layer could finally be built on.

What DIDs and VCs actually are

- DID (Decentralized Identifier):

Is a globally unique identifier that you control, not tied to a central registry (like DNS or Google). It resolves to a DID Document, which contains public keys, service endpoints, etc. It’s not an identity itself — it’s a digital handle that can be cryptographically verified. - VC (Verifiable Credential):

Is a tamper-evident, cryptographically signed statement about some subject. For example: “Alice Smith’s age is over 18,” signed by the UK Government. A verifier can check it’s real and hasn’t been altered, without calling the issuer every time.

Together, they give us a portable trust framework:

DIDs = identifiers you own

VCs = claims that others make about you

Why this matters

Historically, online identity has meant:

- “Google says this user is Alice”

- “Facebook says this user is Alice”

- “Alice created a new username and password here”

Each of those is a centralized proxy for identity — controlled by someone else.

With DIDs + VCs:

- The user holds and presents credentials.

- Verifiers can independently check authenticity.

- No single platform owns your identity or data.

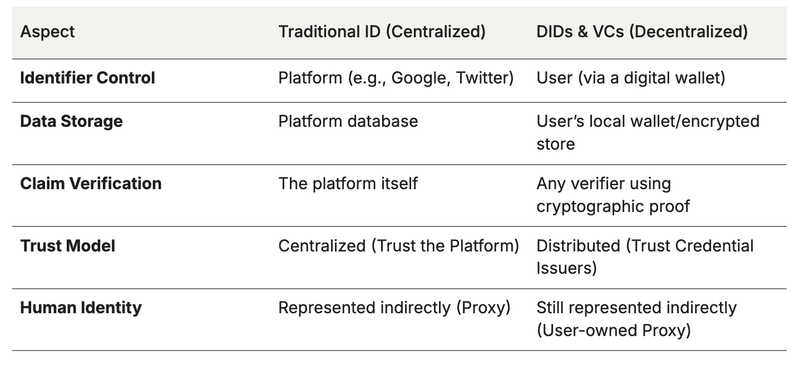

That’s a significant structural shift — it decentralizes the control of identity representation.

But: DIDs and VCs still don’t prove who you are

DIDs and VCs represent identity, but they don’t constitute it. A DID by itself is just a cryptographic keypair with metadata — the system doesn’t know or care who controls it. That’s still just proof of key control, not proof of personhood. You only get “real identity” once a trusted entity issues a verifiable credential binding that DID to a real-world attribute — e.g.:

“did:example:1234abcd belongs to Alice Smith” — signed by the UK Passport Office.

So it’s still a proxy system, but it replaces platform-controlled proxies (like Facebook or Google) with cryptographically verifiable, user-controlled proxies which is much better.

What this changes (and what it doesn’t)

It’s still an abstraction, but it’s a more open, portable, and verifiable abstraction. You could say DIDs and VCs are “a meta-layer for identity”, not “identity itself.”

In conclusion

DIDs/VCs move us closer to a native identity layer in the web stack — because they define open, interoperable standards for representing and verifying identity claims without central intermediaries.

But they don’t magically make the web “know who people are.” They just make it possible for identity information — when issued by trusted parties — to be verified cryptographically, across systems.

So, they provide the plumbing for an identity layer, but not the content of identity.