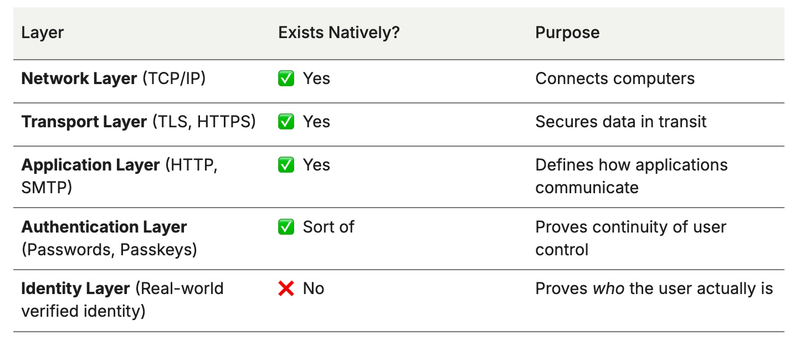

The identity layer — the part that says “who is this person, really?” — does not exist natively in the web’s design. Let’s unpack what that means and why it’s such a big deal

The internet’s original design (TCP/IP, DNS, HTTP, etc.) connects machines, not identities.

- IP addresses identify computers or networks.

- Domain names identify servers or websites.

- HTTP sessions identify browser connections.

None of these say who the human behind the connection is. So from the ground up, the internet gives us: “This device is talking to that server.” Not: “Alice Smith is talking to PayPal.”

Identity got bolted on later — inconsistently

Because the core internet protocols didn’t include identity, every application had to invent its own way to identify users:

- Websites use usernames and passwords.

- Apps use email or phone verification.

- Enterprises use LDAP or Active Directory.

- Social media use OAuth (“Sign in with Google / Facebook”).

The result is fragmented, redundant, and insecure identity handling — every app has its own database of who you are. That’s why:

- You have hundreds of separate logins.

- Data breaches are constant.

- “Identity theft” is even possible at all.

If the web had a native identity layer, most of that wouldn’t happen.

So what do we actually have?

We have authentication systems, not an identity layer. So the internet can authenticate — but it can’t identify anyone by default.

Why this matters (and why people keep trying to fix it)

Because there’s no identity layer, we get:

- Fake accounts, bots, spam

- Data silos and password fatigue

- Fraud and impersonation

- Poor user experience across platforms

This has led to decades of attempts to “add” an identity layer on top of the web, like:

- OpenID / OAuth e.g., “Sign in with Google”

- SAML / enterprise SSO

- Decentralized identity (DID) and verifiable credentials

- Self-sovereign identity (SSI) projects

- Government-backed digital IDs (e.g., EU Digital Identity Wallet, eIDAS 2.0)

Each is trying to retrofit the missing piece: A standard, portable, privacy-preserving way to prove who you are online.

What a true “identity layer” would mean

A genuine identity layer would:

- Let users control their verified credentials.

- Let websites request identity proofs (e.g., “over 18”, “verified professional”).

- Allow cryptographic authentication tied to those proofs.

- Work across platforms and borders.

Think of it as a global digital passport system — decentralized, privacy-preserving, and cryptographically secure. We’re not there yet, but initiatives like W3C Decentralized Identifiers (DIDs) and Verifiable Credentials (VCs) are heading that way.